Is modern tragedy possible? Arthur Miller seemed to think so. He wrote a now-legendary piece for The New York Times in 1949 called “Tragedy and the Common Man,” published seventeen days after the debut of Death of a Salesman on Broadway, in which he argued passionately:

“As a general rule…I think the tragic feeling is evoked in us when we are in the presence of a character who is ready to lay down his life, if need be, to secure one thing-his sense of personal dignity. From Orestes to Hamlet, Medea to Macbeth, the underlying struggle is that of the individual attempting to gain his ‘rightful’ position in his society. Sometimes he is one who has been displaced from it, sometimes one who seeks to attain it for the first time, but the fateful wound from which the inevitable events spiral is the wound of indignity and its dominant force is indignation. Tragedy, then, is the consequence of a man’s total compulsion to evaluate himself justly. … The flaw, or crack in the characters, is really nothing-and need be nothing, but his inherent unwillingness to remain passive in the face of what he conceives to be a challenge to his dignity, his image of his rightful status.”

Miller goes on throughout the essay to dispute the Aristotelian contention that tragedy can be written only about those of high rank. He repeatedly disparages the Poetics’ Chapter 13definition of the tragic hero: “Such a person is someone not preeminent in virtue and justice, and one who falls into adversity not through evil and depravity, but through some kind of error; and one belonging to the class of those who enjoy great renown and prosperity, such as Oedipus, Thyestes, and eminent men from such lineages.” He passionately proposes a different definition of tragic heroism: “The Greeks could probe the very heavenly origin of their ways and return to confirm the rightness of laws. And Job could face God in anger, demanding his right and end in submission. But for a moment everything is in suspension, nothing is accepted, and in this stretching and tearing apart of the cosmos, the character gains “size,” the tragic stature which is spuriously attached to the royal or the high born in our minds. The commonest of men may take on that stature to the extent of his willingness to throw all he has into the contest, the battle to secure his rightful place in the world.”

Admittedly, it is difficult to imagine tragedy in a society in which an individual’s “rightful place in the world”4 is predetermined by birth, and one cannot move up from that place either through struggle or through merit. Attic Greece premiered democracy, but the tragedies which that civilization produced were all about aristocrats. Ordinary citizens simply did not have access to the kind of power that enabled them to “enjoy great renown and prosperity.”5 Is tragedy even possible in a democracy, especially one with no history of social rank? In the modern world, what makes a tragic hero sufficiently larger than life for the paradigm to work?

In Agamemnon, and in Oedipus, tragic stature has clearly been conferred on all monarchs at their ascent to the throne, whether by birthright or by conquest. Even though Oedipus enters Thebes as a commoner, he is later discovered to be the lawful heir to the kingdom of Thebes. For all monarchs, l’etat c’est moi. Because they are kings, Agamemnon and Oedipus are also the state, and the tragedy can center around their behavior as human beings—mere mortals, not demigods–wrestling with the responsibilities of rank. This works for Henry V and Hamlet and Antigone and Creon, and for virtually every work of Sophocles, because, as Aristotle would later put it: ““Not many families provide subjects for tragedies. In their experiments, it was not art but chance that made the poets discover how to produce such effects in their plots; thus they are now obliged to tum to the families which such sufferings have befallen.”

However. it is easy to see why Miller misread “great renown and prosperity” to mean birthright rank, since no other path to leadership would have been possible in truly ancient Greece, well before the fifth century. He contends: “Insistence upon the rank of the tragic hero, or the so-called nobility of his character, is really but a clinging to the outward forms of tragedy. If rank or nobility of character was indispensable, then it would follow that the problems of those with rank were the particular problems of tragedy. But surely the right of one monarch to capture the domain from another no longer raises our passions, nor are our concepts of justice what they were to the mind of an Elizabethan king.”

Tragedies written since ancient Greece have experimented with all kinds of leaders besides monarchs. One option is to write tragedy in fancy dress. Anouilh’s Becket and Robert Bolt’s A Man for All Seasons, especially in their lush movie versions with great actors taking on those big roles, demonstrated pretty convincingly that you can make someone larger than life simply by looking at them through the lens of history but, like classical tragedies, Becket and A Man for All Seasons told the stories of kings although their heroes are commoners. Because their authors were European, they had monarchies in their own history to look back to. And Thomas à Becket and Thomas More do not become worthy opponents to their kings (described by Nolan in Oppenheimer as “two scorpions in a bottle”) until they attain ranks above their stations–Archbishop of Canterbury and Lord High Chancellor–and the battle transcends them to become an ethical struggle between church and state.

In this country we do not have kings who can legally execute their political opponents, nor do we have religious courts with the power to take lives. Miller had to reach back to the seventeenth century to set The Crucible in what would later become the United States with constitutional protections against such capital crimes as witchcraft, just as Shaw had had to return to the Middle Ages to make his point in Saint Joan. By the time these plays were written, military prowess and the church had become access paths to power for ordinary people (as in the case also of Othello) but it was still necessary for the tragic hero “attempting to gain his rightful place” to find the path into the star chambers in which the high-stakes decisions were going to be made and where a commoner could have game-changing influence. According to Miller, “It is time, I think, that we who are without kings, took up this bright thread of our history and followed it to the only place it can possibly lead in our time-the heart and spirit of the average man.”It would have been easier for Miller to test this theory against one of his own artifacts if he had chosen The Crucible, but he hadn’t yet written it when he wrote Tragedy and the Common Man.

As long as the issues that drive a hero to put his or her life on the line still concern us, we can see protagonists of serious plays and novels as tragic. John Proctor does come across as a man of larger-than-life heroism who has made an error that any one of us could make without paying so exorbitant a cost. In Miller’s own words: “Tragedy enlightens–and it must, in that it points the heroic finger at the enemy of man’s freedom. The thrust for freedom is the quality in tragedy which exalts. The revolutionary questioning of the stable environment is what terrifies.”Santiago in Hemingway’s Old Man and the Sea comes close to being the kind of ordinary tragic hero that Miller envisions. Willy Loman is simply too flawed and mediocre for audiences to feel much fear—only pity.

But Miller’s goal in the essay is to attach morality to power, as Aristotle does, and that will not work for Santiago, who battles an implacable and amoral opponent in nature and will be a hero whether he defeats the sharks or not. In The Rebel as Tragic Hero, I myself askedwhether it was possible to write tragedies about ordinary people that would provide sufficient terror to make a contemporary audience feel powerless. Like the ocean in The Old Man and the Sea, the pandemic in La Peste is certainly big enough, and perhaps the novel is really just about the implacable amoral power of disease and not about the Nazi occupation of France. The 2020 Plague Year certainly taught humanity what it feels like to be at the mercy of a natural force over which our technology gives us no control because we lack the knowledge to exert power over it. But the ordinary hero of La Peste, Dr. Bernard Rieux, is just an ordinary hero, an everyman. There is nothing larger than life about him just as there is nothing larger than life about Willy Loman. There is no Prometheus ex machina to give him the knowledge and the power to save humanity from death. He must be content to be Sisyphus and, as Camus suggests, “we must imagine him happy.” Miller would not have called him a tragic hero nor would he have considered the novel a tragedy.

In Miller’s view, the struggle against indignity requires an immoral opponent, not an amoral one: “Now, if it is true that tragedy is the consequence of a man’s total compulsion to evaluate himself justly, his destruction in the attempt posits a wrong or an evil in his environment. And this is precisely the morality of tragedy and its lesson. The discovery of the moral law, which is what the enlightenment of tragedy consists of, is not the discovery of some abstract or metaphysical quantity. The tragic right is a condition of life, a condition in which the human personality is able to flower and realize itself. The wrong is the condition which suppresses man, perverts the flowing out of his love and creative instinct.”13 In Death of a Salesman, for example, that immoral force would be capitalism. Ben Loman’s wealth is a personal victory for him, but hardly a victory of entrepreneurship over large-scale capitalism because he has no influence beyond his family and he is not in a position of social leadership. He is not asked to part the Red Sea or lead the March on Washington to take his people to the Promised Land, or even just to take them across the Ohio to freedom, so he lacks the stature required of tragic heroes that brings renown and, potentially, glory.

If, then, tragedy is about the consequences of actions by people in positions of leadership, then there are many more stories to be found in a complex modern society than there were in ancient Greece. How many top-tier stakeholders are in play? What are the potential consequences of the decisions being made? How much collateral damage to the decision? In other words—what are the stakes, and what would be so high-stakes a game that an ordinary citizen could influence it? What could raise our passions to a level of rage against fate that would require katharsis? What has power over human life that approximates the power of Zeus, unchecked by Judao-Christian notions that gods embody and demand morality? Turning to another Aristotelian concept: What about Spectacle? “The element of the wonderful is required in Tragedy.” By 1945, and certainly by 1968, not only could Shiva or Zeus destroy the world, we could destroy it ourselves. Scientific power had added a dimension to 20th century war that had not been seen since gunpowder and, with it, a new philosophy of what might constitute so-called “just” war. The prospect of nuclear war also brought the obliteration of the warrior culture represented by characters such as Patroclus and Achilles and its definitions of heroism and sacrifice. Alfred Nobel’s complex feelings about dynamite had been brought to theatrical attention through Major Barbara. Oppenheimer had died quietly in 1967 of throat cancer in Princeton where he had been at the Institute for Advanced Study for the last twenty years, like Oedipus living out his days at Colonus. Oppenheimer’s very public guilt, his vigorous opposition to the hydrogen bomb, and his intense lobbying for nuclear disarmament had come back into public notice through his obituaries. Was his story a tragedy for an age in which high-stakes behavior is demanded not only of political leaders but also of scientists?

Miller and Aristotle are certainly in agreement that the essence of tragedy is in its ability to arouse feelings so powerful that they must be assuaged. The stories that tragedies tell are often explained by a concept we now know as Sayre’s law: In any dispute the intensity of feeling is inversely proportional to the value of the issues at stake. The error or frailty that displays itself as hamartia in an otherwise good person is often the disproportionate pursuit of something of little value except to that person, such as flattery to Lear and obedience to Creon. Chorus after chorus in Greek tragedy warns against protagonists’ putting their egos above the best interest of those they serve, valuing power over goodness, and treating their loved ones without respect or compassion. The Aristotelian system of “virtue ethics” demands that, if the stakes are truly high, we must ask ourselves to bring our best behavior to what Miller describes as “a moment everything is in suspension, nothing is accepted… [the] stretching and tearing apart of the cosmos” –the tragic moment.

The grandeur of the collision between human beings striving to be their best selves is what makes catharsis possible. If, as Thomas Sowell warns us, “There are no solutions. There are only tradeoffs,” then Creon and Antigone, Becket and Henry II, Thomas More and Henry VIII, Agamemnon and Clytemnestra and Orestes must all experience reversal, recognition, and suffering. Recognition is the key word here because tragedy is a journey through suffering to self-understanding. Sowell says it himself in ‘The Vision of the Anointed”: “In the tragic vision, individual sufferings and social evils are inherent in the innate deficiencies of all human beings, whether these deficiencies are in knowledge, wisdom, morality, or courage. Moreover, the available resources are always inadequate to fulfill all the desires of all the people. Thus there are no “solutions” in the tragic vision, but only trade-offs that still leave many unfulfilled and much unhappiness in the world.”

J. Robert Oppenheimer is an exemplar for what Sowell called the “unconstrained vision” in which “intention is the essence of virtue…” As Paul Adams summarizes it: “The unconstrained vision emphasizes the plasticity and perfectibility of man. Where those with the constrained vision see trade-offs, those with the unconstrained see solutions; where the first see results, they see purpose; where systemic processes, intentions. They discount the costs–all too evident in the last century–of attaining utopia.” When told by Henry Stimson that bombing Japan could end the war, Oppenheimer says earnestly and cluelessly: “This could end all war. If we retain moral advantage.”

Like all the tragic heroes in the acknowledged canon, Oppenheimer seeks the ideal even at great personal cost. Henry II would like Becket to be able to serve both church and king; that would require a trade-off, so it is unattainable. Antigone and Sir Thomas More would like to serve their kings and live but that is impossible because Creon and Henry VIII rule with constrained vision and require compromise. In the history of tragedies built on the conflict between those two visions, Oppenheimer falls neatly into place alongside Antigone, Othello, Becket, and Thomas More—none of them kings either and two of them real people.

Oppenheimer is a man of unconstrained vision working for a government that is mired in trade-offs. When told by Henry Stimson that bombing Japan could end the war, Oppenheimer echoes Bohr from earlier in the film: “This could end all war. If we retain moral advantage.”18 It is a big “if,” a Utopian “if,” and neither Stimson nor Truman cares in the slightest; they want to end this war. Ending all war because of the immorality of using this weapon on people is not even on their radar.

Oppenheimer: “Once it’s used, nuclear war, maybe all war, becomes unthinkable.

Teller: “Until somebody builds a bigger bomb.”

It is not until the bombs are actually dropped on Japan that Oppenheimer finally experiences anagnoris, following by suffering so powerful that it invades his unconscious in ways he has not experienced since graduate school. Almost immediately, he begins to speak out, leading to the reversal of fortune that occupies most of the film as he finds morality and falls from grace.

As far as morality is concerned, this is not a Christian story. The prevailing theology is Hindu. Any moral complications that are brought in come from the human beings and derive from the ancient laws of Judaism. Human beings are capable of virtue. They have an earthly duty to consider when they are handed the power that once belonged only to the gods. The story of Oppenheimer is not a story about him any more than the story of Prometheus is about Prometheus. Each is the story of Pandora’s box or the expulsion from Eden. What happens when you give human beings powers that they themselves have always attributed only to deities?

Oppenheimer: “I’m teaching something no one here’s dreamt of. But once people start hearing what you can do with it…”

Lawrence: “There’s no going back.”

Since the beginnings of recorded history, human beings have sought the powers of gods. We can fly now, we can stop time and put two people in two different places simultaneously. We can create life. But we can’t stop death. We cannot yet transmogrify or transport ourselves by disassembling and reassembling our energy. We can’t travel to the future or even see into it. And now we can destroy ourselves with fire. We have the technology to tear into the earth’s protective layers. We have become death, the destroyer of worlds. As Trinity is counting down, Groves says to Oppenheimer: “Robert, try not to blow up the world.”

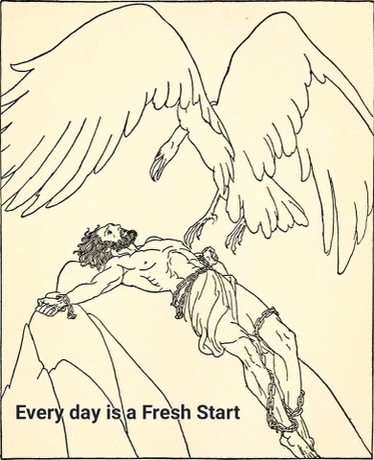

As tragic heroes go, Oppenheimer himself in the film, in the books, and in the vast array of contemporaneous information about him as a real person, rather resembles Oedipus. In the world in which he finds himself, he is caught between the way he sees himself and the way others see him. Strauss says of him, sounding exactly like Tiresias: “Genius is no guarantee of wisdom. How could this man who saw so much be so blind?” Like Oedipus, Oppenheimer is the brilliant outsider, arrogant, distrustful, driven even when warned, passionate, easily angered, persistent, and impulsive, vengeful yet compassionate by turns, virtually void of frustration tolerance, tortured by attention surplus disorder. Niels Bohr sees it in him at once as he toys with the poisoned apple: “Go somewhere where they’ll let you think…It’s not about whether you can read music. Can you hear the music, Robert?” Chevalier says it again later on: “Robert, you see beyond the world we live in. There’s a price to be paid for that.” Prometheus is the obvious analogy. Caught between a world that has been overthrown and one in which Titans no longer have a place, he throws in his lot with humanity and invites the wrath of Zeus.

The Prometheus story doesn’t seem to have interested the best Greek playwrights as a subject for tragedy: after all, he wasn’t mortal and the one play we have—probably not by Aeschylus—doesn’t satisfy Aristotle’s criteria: in particular, the one that says you can have a tragedy without characters but not without action. In the only mention of the play in Poetics, Aristotle calls it “simple.” Tragedy requires an implacable universe, which may be amoral or immoral, but in the Prometheus myth Zeus represents amoral power and Prometheus himself the human compassion without which pity and fear are not possible, so the story is really not about actual human beings whose suffering is real because their livers cannot regenerate to be eaten again the following day. Linda Loman, like Kitty Oppenheimer, stands by her man but it is she who displays the only tragic nobility in the play and it is not her story. Miller wasn’t exactly wrong that it is sad and immoral when we see giant corporations supplant neighborhood grocery stores and create food deserts and Ibsen wasn’t wrong either when he offers up Thomas Stockmann as a minor league tragic hero pecked to death by bureaucrats, but while Aristotle acknowledges pathetic tragedies, he dismisses them as inherently mediocre because there is no reversal, recognition, or suffering.

It was Mary Shelley who originated the idea of fire as a metaphor for scientific hubris when she subtitled her 1818 novel The Modern Prometheus. When Bird and Sherwin wrote American Prometheus in 2005, the comparison to the work at Los Alamos had already been around for sixty years. September 1945’s Scientific Monthly contained the sentence: “Modern Prometheans have raided Mount Olympus again and have brought back for man the very thunderbolts of Zeus.” Christopher Nolan begins his film with the sonorous line: PROMETHEUS STOLE FIRE FROM THE GODS AND GAVE IT TO MAN. FOR THIS HE WAS CHAINED TO A ROCK AND TORTURED FOR ETERNITY.”

But Shelley wasn’t interested in Prometheus the Fire Bringer but in Prometheus the loyal baby Titan to whom Zeus gave the job of creating the human race. According to the legend, he and Athena created humankind from earth and water and blew life into the wet clay. The only element missing from the process is fire, which Prometheus gave us later on as part of an entirely different story, but what is interesting about Frankenstein is that, for Mary Shelley, bringing a collection of body parts to life without the breath of a god required electricity. To play God, Victor Frankenstein had to use fire, the one element that Zeus had hidden from humanity according to the Prometheus story, but which the Titan returned to us in defiance of Zeus at the cost of eternal suffering. In the less famous of the two stories, Prometheus is credited with bringing to humanity not only technology but learning–medicine, architecture, mathematics, astronomy, metallurgy and navigation. In other words—power.

In the 20th century, who has more power than kings? In ancient Greece, scientists were just beginning to understand the power in nature and bend it to their control. But this knowledge was in its infancy and, in the narrative, it is Prometheus who is the giver of the learning and the technology that will threaten the raw power of Zeus. The gift of fire that, used in moderation, allows humans to tame nature to their purpose, always remains too dangerous to trust. When given too much fuel or too much air or too much freedom, it destroys. The king-gods in most earth-centered religions control fire. Now humans control it and, as nuclear fission, fire that has supposedly been tamed becomes fire unleashed. The scientists seeking to create it had no idea if it could be controlled. The fear that pervades Oppenheimer is the fear articulated to him by Einstein and Bohr:

Bohr: I’m not here to help, Robert. I knew you could do this without me.

Oppenheimer: Then why did you come?

Bohr: To talk about after. The power you’re revealing will forever outlive the Nazis. And the world is not prepared.

Oppenheimer: (echoing Bohr from earlier in the film) You can lift the rock without being ready for the snake that’s revealed.

Bohr: We have to make the politicians understand- this isn’t a new weapon. It’s a new world. I’ll be out there, doing what I can- but you…You’re an American Prometheus- Father of the Atomic Bomb. The man who gave them the power to destroy themselves. They’ll respect that. And your work really begins.”

Oppenheimer is baffled. He thinks his work is nearing its end and that to move ahead will mean using nuclear fusion to create a hydrogen bomb, which he has come to oppose. He started out as a leader of leaders gathering his team of geniuses to accomplish the mission that Groves calls: “the most important fucking thing that’s ever happened in the history of the world.” This global undertaking is bigger than Agamemnon gathering his fleet at Aulis to launch the invasion of Troy. Agamemnon sacrificed a daughter. Oppenheimer sacrificed the love of his life.

Groves quotes a colleague as saying of Oppenheimer that he couldn’t run a hamburger stand. Oppenheimer agrees, but says “I can run the Manhattan Project.” In the film, his chorus of fellow physicists warn him repeatedly that his motives are egoistic and far from pure. From the hubris comes the hamartia. What Bohr tries to tell him is that the real work will come after the weapon is created and in human hands. Once the secret to nuclear fission has been discovered by unconstrained thinkers in the scientific community, Oppenheimer’s follow-up job is not as project leader but as resource manager—not a job for a tragic hero. He is Hephaestos, the god of “fire put to use.” He must be the caretaker of the Gadget sought so desperately by all the world’s governments. That is a job for a constrained thinker, not a visionary. Reversal of fortune is virtually inevitable.

Strauss says of him: “He wanted all the glory and none of the responsibility. So he needed absolution. He needed to be a martyr. To suffer, and take the sins of the world on his shoulders. To say ‘no, we cannot continue on this road’ even as he knew we’d have to… He knew he’d have to be seen to suffer for what he did. It was all part of his plan. He wanted the glorious insincere guilt of the self-important to wear like a fucking crown. And I gave it to him…” Racked with guilt for doing what he was asked to do in the best interest of the state, he turns to his wife Kitty for sympathy but instead gets words of justice: “You don’t get to commit the sin, then have us all feel sorry for you that it had consequences.” Tragic heroes never see their own hubris until anagnorisis forces self-knowledge on them, either before or after the inevitable peripety.

Oppenheimer told NBC in a 1965 documentary: “We knew the world would not be the same. A few people laughed, a few people cried. Most people were silent,”. “I remembered the line from the Bhagavad-Gita; Vishnu is trying to persuade the prince that he should do his duty, and to impress him, takes on his multi-armed form and says, “Now I have become death, the destroyer of the worlds’. I suppose we all thought that, one way or another.”A friend of the scientist said the quote sounded like one of Oppenheimer’s “priestly exaggerations.” But there is more. After Trinity, Oppenheimer’s friend and longtime colleague Isidor Rabi caught sight of him from a distance: “I’ll never forget his walk; I’ll never forget the way he stepped out of the car… his walk was like High Noon… this kind of strut. He had done it.”

In Oppenheimer, the hero progresses slowly through reversal of fortune to full recognition through the patient portrayal of the testimony from hearings that resulted in the revocation of his Q clearance in 1954, interspersed with conversations with colleagues—some real, some fictionalized. After Bohr, it is his lifelong friend Rabi who is the Messenger:

Rabi: You drop a bomb and it falls on the just and the unjust. I don’t wish the culmination of three centuries of physics to be a weapon of mass destruction.

Oppenheimer: Izzy, I don’t know if we can be trusted with such a weapon, but I know the Nazis can’t. We have no choice.

Rabi: Well, the second thing you have to do is appoint Hans Bethe to head the Theoretical division.

Oppenheimer: Wait, what was the first?

Rabi: Take off that ridiculous [Army] uniform. You’re a scientist.

Oppenheimer: General Groves is insisting we join.

Rabi: Tell Groves to shit in his hat. They need us for who we are. So be yourself, only… better.

When Oppenheimer begs Edward Teller to stay at Los Alamos to work on the fusion bomb despite his personal qualms, he exposes himself as a visionary trying hopelessly to gain traction in a world of constrained thinkers and doomed to fail by his own internal conflict. Teller says to him: “You’re a politician now, Robert. You left physics behind long ago.” Although it is doubtless a fictional conversation, Nolan selects as the last Messenger no other than Albert Einstein:

Oppenheimer: “When we detonate an atomic device, we might start a chain reaction that destroys the world.”

Einstein: “And here we are, lost in your quantum world of probabilities, but needing certainty… You’re a man chasing a woman who doesn’t love him any more- the United States government.

Oppenheimer: I’m not sure you understand, Albert.

Einstein No? I left my country, never to return. The German calamity of years ago repeats itself- people acquiesce without resistance and align themselves with the forces of evil. You’ve served America well, and if this is the reward she has to offer perhaps you should turn your back on her.

Oppenheimer: Dammit, I happen to love this country.

Einstein considers this. Nods slowly.

Einstein: Then tell them to go to hell.

As the film comes to an end, Oppenheimer is beginning to find the voice that will enable the audience to forgive him his arrogance and ambition because of the suffering he has brought upon himself. As it turned out, Oppenheimer never came close to his potential as a scientist. After abandoning his work on black holes in the late thirties, he left the theory to be discovered and for black holes to be documented years later by others and spent the rest of his life in reflective study but without publishing anything after 1950.

Gray: Dr Oppenheimer, when did your strong moral convictions develop with respect to the hydrogen bomb?

Oppenheimer: When it became clear to me that we would tend to use any weapon we had.

Strauss: J. Robert Oppenheimer- the martyr. I gave him exactly what he wanted. To be remembered for Trinity, not Hiroshima, not Nagasaki. He should be thanking me. Amateurs seek the sun and get eaten; power stays in the shadows.”

Like A Man for All Seasons, Oppenheimer the film turns out to be a story about human treachery, at least on the surface but, as a tragedy, it is so much less about Oppenheimer and Strauss than it is about Oppenheimer and Einstein and Bohr. At the very end of the film, the last word goes to Einstein:

“You once had a reception for me at Berkeley. Gave me an award. You all believed I’d lost the ability to understand what I’d started. So that award wasn’t for me… it was for all of you. Now it’s your turn to deal with the consequences of your achievements. And one day… when they’ve punished you enough (perhaps when the eagle has finally had enough liver) they’ll serve salmon and potato salad, make speeches, give you a medal…Pat you on the back and tell you all is forgiven …Just remember. It won’t be for you.”37

There are not so many Greek tragedies about democracy—perhaps only Eumenides but this story is the more like the story of The Libation Bearers; its hero racked with guilt for doing what he was asked to do in the best interest of the state with his wife bitchslapping him and saying: “You don’t get to commit the sin, then have us all feel sorry for you that it had consequences.”

But perhaps modern tragedy is necessarily collective. Surely, justice is a collective national responsibility in a democracy and a shared collective global responsibility in this dangerous 21st century. Each of us must find our place in the collective, whether we stand with Rabi, Truman, or Oppenheimer. When a tragedy is about “the right of one monarch to capture the domain from another,” then Creon is the state; Agamemnon is the state; Oedipus is the state; Macbeth is the state; Lear is the state; Truman is the state. But if “our concepts of justice” are no longer “what they were to the mind of an Elizabethan king” then it falls to humanity to bring it about when the gods cannot be relied on. In that case, tragedies remind us that we must help one another to be heroes.

Great tragedy is not sad. It is inspiring and uplifting and asks us, in the midst of our grief over any human being’s inability to triumph over fate, or evil, or indifference, to honor their effort. We are happy that Lear finds his best self in the end, as does Oedipus, and while we mourn the real-life death of Martin Luther King, we rejoice in the life he chose to lead that made an early death inevitable but moved the needle a little for all of us. The best, and probably most forgotten part of the Prometheus story is the only thing that Pandora manages to keep in the jar. That is Hope. Until Heracles or Godot comes, or if they never come, as long as we have not set the atmosphere on fire, every day is a fresh start.

Leave a comment